"The primary merit for the picture is to be a feast for the eyes." Delacroix “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” - Steve Jobs "Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand." –Dr. Albert Einstein "Wonder is comes from the awareness of ignorance of religious mass"

2012. augusztus 27., hétfő

2012. augusztus 26., vasárnap

2012. augusztus 24., péntek

Books vs. Cigarettes - George Orwell's Essay

Books vs.

Cigarettes

Essay

A couple of

years ago a friend of mine, a newspaper editor, was

firewatching with some factory workers. They fell to talking about his newspaper, which most of them read and approved of, but when he asked them what they thought of the literary section, the answer he got was: "You don't suppose we read that stuff, do you? Why, half the time you're talking about books that cost twelve and sixpence! Chaps like us couldn't spend twelve and sixpence on a book." These, he said, were men who thought nothing of spending several pounds on a day trip to Blackpool. This idea that the buying, or even the reading, of books is an expensive hobby and beyond the reach of the average person is so widespread that it deserves some detailed examination. Exactly what reading costs, reckoned in terms of pence per hour, is difficult to estimate, but I have made a start by inventorying my own books and adding up their total price. After allowing for various other expenses, I can make a fairly good guess at my expenditure over the last fifteen years. The books that I have counted and priced are the ones I have here, in my flat. I have about an equal number stored in another place, so that I shall double the final figure in order to arrive at the complete amount. I have not counted oddments such as proof copies, defaced volumes, cheap paper-covered editions, pamphlets, or magazines, unless bound up into book form. Nor have I counted the kind of junky books-old school text-books and so forth--that accumulate in the bottoms of cupboards. I have counted only those books which I have acquired voluntarily, or else would have acquired voluntarily, and which I intend to keep. In this category I find that I have 442 books, acquired in the following ways: Bought (mostly second-hand) 251 Given to me or bought with book tokens 33 Review copies and complimentary copies 143 Borrowed and not returned 10 Temporarily on loan 5 Total 442 Now as to the method of pricing. Those books that I have bought I have listed at their full price, as closely as I can determine it. I have also listed at their full price the books that have been given to me, and those that I have temporarily borrowed, or borrowed and kept. This is because book-giving, book-borrowing and bookstealing more or less even out. I possess books that do not strictly speaking belong to me, but many other people also have books of mine: so that the books I have not paid for can be taken as balancing others which I have paid for but no longer possess. On the other hand I have listed the review and complimentary copies at half-price. That is about what I would have paid for them second-hand, and they are mostly books that I would only have bought second-hand, if at all. For the prices I have sometimes had to rely on guesswork, but my figures will not be far out. The costs were as follows: £ s. d. Bought 36 9 0 Gifts 10 10 0 Review copies, etc 25 11 9 Borrowed and not returned 4 16 9 On loan 3 10 0 Shelves 2 0 0 Total 82 17 6 Adding the other batch of books that I have elsewhere, it seems that I possess altogether nearly 900 books, at a cost of £165 15s. This is the accumulation of about fifteen years--actually more, since some of these books date from my childhood: but call it fifteen years. This works out at £11 Is. a year, but there are other charges that must be added in order to estimate my full reading expenses. The biggest will be for newspapers and periodicals, and for this I think £8 a year would be a reasonable figure. Eight pounds a year covers the cost of two daily papers, one evening paper, two Sunday papers, one weekly review and one or two monthly magazines. This brings the figure up to £19 1s, but to arrive at the grand total one has to make a guess. Obviously one often spends money on books without afterwards having anything to show for it. There are library subscriptions, and there are also the books, chiefly Penguins and other cheap editions, which one buys and then loses or throws away. However, on the basis of my other figures, it looks as though £6 a year would be quite enough to add for expenditure of this kind. So my total reading expenses over the past fifteen years have been in the neighbourhood of £25 a year. Twenty-five pounds a year sounds quite a lot until you begin to measure it against other kinds of expenditure. It is nearly 9s 9d a week, and at present 9s 9d is the equivalent of about 83 cigarettes (Players): even before the war it would have bought you less than 200 cigarettes. With prices as they now are, I am spending far more on tobacco than I do on books. I smoke six ounces a week, at half-a-crown an ounce, making nearly £40 a year. Even before the war when the same tobacco cost 8d an ounce, I was spending over £10 a year on it: and if I also averaged a pint of beer a day, at sixpence, these two items together will have cost me close on £20 a year. This was probably not much above the national average. In 1938 the people of this country spent nearly £10 per head per annum on alcohol and tobacco: however, 20 per cent of the population were children under fifteen and another 40 per cent were women, so that the average smoker and drinker must have been spending much more than £10. In 1944, the annual expenditure per head on these items was no less than £23. Allow for the women and children as before, and £40 is a reasonable individual figure. Forty pounds a year would just about pay for a packet of Woodbines every day and half a pint of mild six days a week--not a magnificent allowance. Of course, all prices are now inflated, including the price of books: still, it looks as though the cost of reading, even if you buy books instead of borrowing them and take in a fairly large number of periodicals, does not amount to more than the combined cost of smoking and drinking. It is difficult to establish any relationship between the price of books and the value one gets out of them. "Books" includes novels, poetry, text books, works of reference, sociological treatises and much else, and length and price do not correspond to one another, especially if one habitually buys books second-hand. You may spend ten shillings on a poem of 500 lines, and you may spend sixpence on a dictionary which you consult at odd moments over a period of twenty years. There are books that one reads over and over again, books that become part of the furniture of one's mind and alter one's whole attitude to life, books that one dips into but never reads through, books that one reads at a single sitting and forgets a week later: and the cost, in terms of money, may be the same in each case. But if one regards reading simply as a recreation, like going to the pictures, then it is possible to make a rough estimate of what it costs. If you read nothing but novels and "light" literature, and bought every book that you read, you would be spending-allowing eight shillings as the price of a book, and four hours as the time spent in reading it-two shillings an hour. This is about what it costs to sit in one of the more expensive seats in the cinema. If you concentrated on more serious books, and still bought everything that you read, your expenses would be about the same. The books would cost more but they would take longer to read. In either case you would still possess the books after you had read them, and they would be saleable at about a third of their purchase price. If you bought only second-hand books, your reading expenses would, of course, be much less: perhaps sixpence an hour would be a fair estimate. And on the other hand if you don't buy books, but merely borrow them from the lending library, reading costs you round about a halfpenny an hour: if you borrow them from the public library, it costs you next door to nothing. I have said enough to show that reading is one of the cheaper recreations: after listening to the radio probably THE cheapest. Meanwhile, what is the actual amount that the British public spends on books? I cannot discover any figures, though no doubt they exist. But I do know that before the war this country was publishing annually about 15,000 books, which included reprints and school books. If as many as 10,000 copies of each book were sold--and even allowing for the school books, this is probably a high estimate-the average person was only buying, directly or indirectly, about three books a year. These three books taken together might cost £1, or probably less. These figures are guesswork, and I should be interested if someone would correct them for me. But if my estimate is anywhere near right, it is not a proud record for a country which is nearly 100 per cent literate and where the ordinary man spends more on cigarettes than an Indian peasant has for his whole livelihood. And if our book consumption remains as low as it has been, at least let us admit that it is because reading is a less exciting pastime than going to the dogs, the pictures or the pub, and not because books, whether bought or borrowed, are too expensive. |

2012. augusztus 20., hétfő

2012. augusztus 12., vasárnap

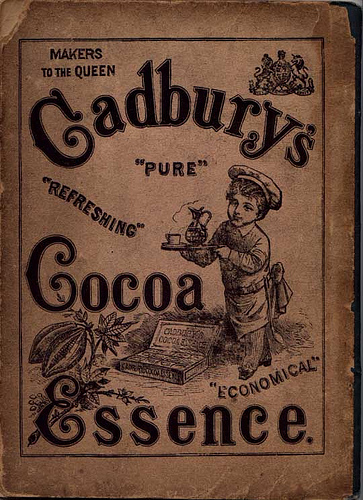

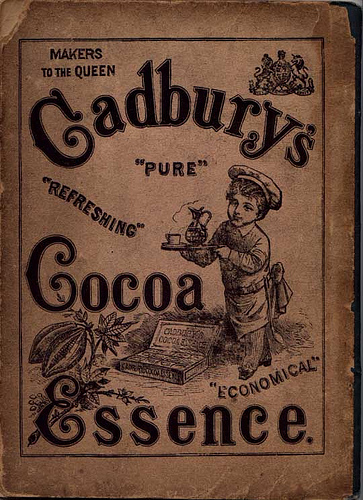

Cadbury, a brit óriás

Cadbury, a brit óriás

A cég alapítója, John Cadbury (1801-1889) egy kvéker család  leszármazottja volt. Ez számunkra csak amiatt érdekes, mivel származása miatt nem mehetett egyetemre, így kénytelen volt mással foglalkozni, választása a kereskedelemre esett. 1818-ban így megnyitotta első tea üzletét Leedsben. Hat évvel később megnyitott egy fűszerüzletet is Birmingham egyik legforgalmasabb utcáján, a Bull Streeten, ahol a tea mellett kakaót és ivócsokoládét is árult már, illetve néhány saját készítésű terméket. Kvékerként fontos volt számára az egészséges életmód, emiatt a teát, kávét, csokoládét az alkohol alternatívájaként szánta a lakosok számára, amit személyes meggyőződése szerint az élet tönkretevőjének tekintett.

leszármazottja volt. Ez számunkra csak amiatt érdekes, mivel származása miatt nem mehetett egyetemre, így kénytelen volt mással foglalkozni, választása a kereskedelemre esett. 1818-ban így megnyitotta első tea üzletét Leedsben. Hat évvel később megnyitott egy fűszerüzletet is Birmingham egyik legforgalmasabb utcáján, a Bull Streeten, ahol a tea mellett kakaót és ivócsokoládét is árult már, illetve néhány saját készítésű terméket. Kvékerként fontos volt számára az egészséges életmód, emiatt a teát, kávét, csokoládét az alkohol alternatívájaként szánta a lakosok számára, amit személyes meggyőződése szerint az élet tönkretevőjének tekintett.

leszármazottja volt. Ez számunkra csak amiatt érdekes, mivel származása miatt nem mehetett egyetemre, így kénytelen volt mással foglalkozni, választása a kereskedelemre esett. 1818-ban így megnyitotta első tea üzletét Leedsben. Hat évvel később megnyitott egy fűszerüzletet is Birmingham egyik legforgalmasabb utcáján, a Bull Streeten, ahol a tea mellett kakaót és ivócsokoládét is árult már, illetve néhány saját készítésű terméket. Kvékerként fontos volt számára az egészséges életmód, emiatt a teát, kávét, csokoládét az alkohol alternatívájaként szánta a lakosok számára, amit személyes meggyőződése szerint az élet tönkretevőjének tekintett.

leszármazottja volt. Ez számunkra csak amiatt érdekes, mivel származása miatt nem mehetett egyetemre, így kénytelen volt mással foglalkozni, választása a kereskedelemre esett. 1818-ban így megnyitotta első tea üzletét Leedsben. Hat évvel később megnyitott egy fűszerüzletet is Birmingham egyik legforgalmasabb utcáján, a Bull Streeten, ahol a tea mellett kakaót és ivócsokoládét is árult már, illetve néhány saját készítésű terméket. Kvékerként fontos volt számára az egészséges életmód, emiatt a teát, kávét, csokoládét az alkohol alternatívájaként szánta a lakosok számára, amit személyes meggyőződése szerint az élet tönkretevőjének tekintett.

A cégre egyébként a későbbiekben is jellemző volt ez a mentalitás, mindig figyelemmel kísérték a fogyasztók és a dolgozók érdekeit is. Érdekes például, hogy a gyerekek védelme érdekében sokáig nem engedték meg, hogy anyák dolgozzanak az üzemekben, emiatt ha egy ott dolgozó lány férjhez ment, egy ajándék kíséretében elbúcsúztak tőle. De a cég kivette a részét a mindennapi élet különböző területein a sporttól kezdve az állatvédelemig.

1831-ben már nagyüzemi mennyiségben folyt a gyártás, emiatt Crooked Laneben nyitott egy üzemet. 1847-ben testvérét, Benjamint is bevette az üzletbe, aminek a nevét megváltoztatta "Cadbury Brothers"-re, majd át is költöztek Londonba, a Bridge Streetbe. Az alapító élete azonban nem tekinthető végig sikertörténetnek, hamarosan meghalt felesége, ő maga is beteg volt, testvérével is eltávolodtak egymástól, ezek következtében a cég üzletileg sem állt jól. Végül 1861-ben visszavonult, és a cég irányítását fiaira, Richardra ésGeorgera bízta. A cég története innentől kezdve egy végtelen hosszúságú családregényként alakult, erről számos helyen találtok részletes leírást (pl. Wikipedia).

Technológiai újdonságok

Érdekes módon az első termékek között szinte elhanyagolható volt a közvetlenül fogyasztható csokoládé, mivel ennek előállítása még nagyon gyerekcipőben járt ebben az időszakban, nem is hasonlított a manapság ismerthez. Sokkal nagyobb mennyiségben állított elő ivócsokoládét, illetve a kakaó különféle változatait (por, paszta stb.).

De ebben az időszakban a kakaó sem igazán úgy nézett ki, mint ahogy mi ismerjük napjainkban. Több mint 50% volt a zsírtartalma, ami jelentősen megterhelte az ínyencek gyomrát. A gyártók különféle trükkökkel próbálták ezt orvosolni, John Cadbury például egyebek mellet burgonyalisztet kevert a kakaóba, azonban ez a minőség rovására ment, mivel a végeredmény nek már csak alig ötöde volt igazi kakaó. A választ végül Amszterdamban találták meg, ahol egy Coenraad Johannes van Houten nevű úriember feltalált egy kézi présgépet, amivel felére tudták csökkenteni a kakaó zsírtartalmát. Angliában ez a technológia még ismeretlen volt, George Cadbury volt az első, aki beszerzett egy ilyen készüléket, majd megkezdte annak használatát. A végeredmény neve: Cadbury's cocoa Essence lett. Az árusítás kicsit nehézkesen indult, mivel meglehetősen drága lett a végeredmény, de a vásárlókat sikerült meggyőzni arról, hogy ez az igazi jó minőség megéri az árát és rövid időn belül olyan népszerűvé vált, hogy 1873-ban felhagytak a teaárusítással és kizárólag csokoládéval foglalkoztak.

nek már csak alig ötöde volt igazi kakaó. A választ végül Amszterdamban találták meg, ahol egy Coenraad Johannes van Houten nevű úriember feltalált egy kézi présgépet, amivel felére tudták csökkenteni a kakaó zsírtartalmát. Angliában ez a technológia még ismeretlen volt, George Cadbury volt az első, aki beszerzett egy ilyen készüléket, majd megkezdte annak használatát. A végeredmény neve: Cadbury's cocoa Essence lett. Az árusítás kicsit nehézkesen indult, mivel meglehetősen drága lett a végeredmény, de a vásárlókat sikerült meggyőzni arról, hogy ez az igazi jó minőség megéri az árát és rövid időn belül olyan népszerűvé vált, hogy 1873-ban felhagytak a teaárusítással és kizárólag csokoládéval foglalkoztak.

nek már csak alig ötöde volt igazi kakaó. A választ végül Amszterdamban találták meg, ahol egy Coenraad Johannes van Houten nevű úriember feltalált egy kézi présgépet, amivel felére tudták csökkenteni a kakaó zsírtartalmát. Angliában ez a technológia még ismeretlen volt, George Cadbury volt az első, aki beszerzett egy ilyen készüléket, majd megkezdte annak használatát. A végeredmény neve: Cadbury's cocoa Essence lett. Az árusítás kicsit nehézkesen indult, mivel meglehetősen drága lett a végeredmény, de a vásárlókat sikerült meggyőzni arról, hogy ez az igazi jó minőség megéri az árát és rövid időn belül olyan népszerűvé vált, hogy 1873-ban felhagytak a teaárusítással és kizárólag csokoládéval foglalkoztak.

nek már csak alig ötöde volt igazi kakaó. A választ végül Amszterdamban találták meg, ahol egy Coenraad Johannes van Houten nevű úriember feltalált egy kézi présgépet, amivel felére tudták csökkenteni a kakaó zsírtartalmát. Angliában ez a technológia még ismeretlen volt, George Cadbury volt az első, aki beszerzett egy ilyen készüléket, majd megkezdte annak használatát. A végeredmény neve: Cadbury's cocoa Essence lett. Az árusítás kicsit nehézkesen indult, mivel meglehetősen drága lett a végeredmény, de a vásárlókat sikerült meggyőzni arról, hogy ez az igazi jó minőség megéri az árát és rövid időn belül olyan népszerűvé vált, hogy 1873-ban felhagytak a teaárusítással és kizárólag csokoládéval foglalkoztak.

Ezzel a lépéssel meglehetősen sokat tettek az angol csokoládégyártás előrelépéséhez. A hírnevet tovább erősítette a hamarosan megjelenő újfajta termékük, a húsvéti csokoládétojás. Különféle ízesítésekkel, marcipán virágokkal jelentek meg az első ilyen tojások 1875-ben. Mindezzel olyan sikereket értek el, hogy a cég profiljában a mai napig megjelennek ezek. Az évek folyamán persze egyre inkább fejlődtek a díszítés területén, különböző egyéb nemzetek hatásaira (német, francia) sikerült még tovább bővíteni a repertoárt.

A kontinens csokoládégyártása azonban ebben az időszakban már meglehetősen előreszaladt, emiatt egy külső szakértőt kellett megszerezniük. 1880-ban Frederic Kinchelman francia mestercukrász segítségével a Cadbury hamarosan bővíthette termékeit különféle egyéb ínyencségekkel: nugátok, pisztácia, bonbonok, karamell és további még jobb minőségű csokoládék.

Csaknem 20 évvel később pedig már elkészültek az első tejcsokoládék is a gyárban, habár ezek első körben nem arattak túlzott sikereket. Az első kísérletek ugyanis csak tejpor, kakaó és cukor megfelelő keverékét jelentették, ami nagy on elmaradt az akkor piacvezetőnek számító svájci tejcsokoládékhoz képest. Az ezredfordulót követően emiatt az ifjabb George Cadbury belekezdett egy saját táblás csoki fejlesztésébe. Néhány éven belül siker övezte a fejlesztéseket, az első világháború idejére már piacvezetők voltak az új termékkel. A Cadbury Milk Tray 1915-ben indult útjára, hogy felvegye a versenyt a svájci vezető márkákkal, ha nem is sikerült olyan nagyra nőnie, de a nemzet szívében mindenképpen helyt talált. Ez a termék közel 100 éves örökség, továbbra is az egyik legnagyobb ajándékozási márka az Egyesült Királyságban.

on elmaradt az akkor piacvezetőnek számító svájci tejcsokoládékhoz képest. Az ezredfordulót követően emiatt az ifjabb George Cadbury belekezdett egy saját táblás csoki fejlesztésébe. Néhány éven belül siker övezte a fejlesztéseket, az első világháború idejére már piacvezetők voltak az új termékkel. A Cadbury Milk Tray 1915-ben indult útjára, hogy felvegye a versenyt a svájci vezető márkákkal, ha nem is sikerült olyan nagyra nőnie, de a nemzet szívében mindenképpen helyt talált. Ez a termék közel 100 éves örökség, továbbra is az egyik legnagyobb ajándékozási márka az Egyesült Királyságban.

on elmaradt az akkor piacvezetőnek számító svájci tejcsokoládékhoz képest. Az ezredfordulót követően emiatt az ifjabb George Cadbury belekezdett egy saját táblás csoki fejlesztésébe. Néhány éven belül siker övezte a fejlesztéseket, az első világháború idejére már piacvezetők voltak az új termékkel. A Cadbury Milk Tray 1915-ben indult útjára, hogy felvegye a versenyt a svájci vezető márkákkal, ha nem is sikerült olyan nagyra nőnie, de a nemzet szívében mindenképpen helyt talált. Ez a termék közel 100 éves örökség, továbbra is az egyik legnagyobb ajándékozási márka az Egyesült Királyságban.

on elmaradt az akkor piacvezetőnek számító svájci tejcsokoládékhoz képest. Az ezredfordulót követően emiatt az ifjabb George Cadbury belekezdett egy saját táblás csoki fejlesztésébe. Néhány éven belül siker övezte a fejlesztéseket, az első világháború idejére már piacvezetők voltak az új termékkel. A Cadbury Milk Tray 1915-ben indult útjára, hogy felvegye a versenyt a svájci vezető márkákkal, ha nem is sikerült olyan nagyra nőnie, de a nemzet szívében mindenképpen helyt talált. Ez a termék közel 100 éves örökség, továbbra is az egyik legnagyobb ajándékozási márka az Egyesült Királyságban.

2009-ben a kakaóvajat pálmaolajjal helyettesítették a jobb íz elérésének reményében, bár ezt külön nem jelezték a csomagoláson. A fogyasztók és a környezetvédők nem örültek a váltásnak, ezért visszatértek a kakaóvajhoz.

Ezt követően a történet a szokásos. Folyamatos küzdelem a piacon, folyamatos fejlesztések, néhány kiemelkedő dobás (pl. török rózsa ízesítésű csokoládék, dobozos csokoládé) és persze a meglévő termékek is további sikereket értek el. Ezek közül továbbra is kiemelkedőek voltak a húsvéti tojások, amelyeket elnézegetve egyértelmű, hogy már messze elérték a művészet szintet. Emellett azonban a cég nem ragaszkodik a 200 éves “tradicionális” cég imázshoz, termékpalettájukon mindig megjelennek a piac aktuális igényeinek megfelelő termékek is (pl. Cadbury Miniatűr Hősök gyűjtemény…).

Küzdelem a multikkal

Bár pénzügyileg a cég sikeres, történelme során számos tulajdonosváltást élt meg. George Cadbury fia, Lawrence a háború után vette át  a vállalkozást, majd 1969-ben egyesült a Schweppes italgyártó céggel, így létrehozva aCadbury Schweppest, mely olyan termékekkel állt elő, mint aSunkist, a Canada Dry vagy aTyphoo Tea. 2007 márciusában a Cadbury Schweppes bejelentette, hogy szeretne szétválni, a vállalat egyik része kizárólag a csokoládé-, a másik pedig az italgyártásra fókuszálna. Ez 2008. május 2-án történt meg, az italgyártó cég Dr. Pepper Snapple Group néven működött tovább.

a vállalkozást, majd 1969-ben egyesült a Schweppes italgyártó céggel, így létrehozva aCadbury Schweppest, mely olyan termékekkel állt elő, mint aSunkist, a Canada Dry vagy aTyphoo Tea. 2007 márciusában a Cadbury Schweppes bejelentette, hogy szeretne szétválni, a vállalat egyik része kizárólag a csokoládé-, a másik pedig az italgyártásra fókuszálna. Ez 2008. május 2-án történt meg, az italgyártó cég Dr. Pepper Snapple Group néven működött tovább.

2007 októberében a Cadbury plc bezárta Keynshamben működő gyárát, ezzel 500-700 munkahely szűnt meg. A termelést angol és lengyel üzemek vették át.

a vállalkozást, majd 1969-ben egyesült a Schweppes italgyártó céggel, így létrehozva aCadbury Schweppest, mely olyan termékekkel állt elő, mint aSunkist, a Canada Dry vagy aTyphoo Tea. 2007 márciusában a Cadbury Schweppes bejelentette, hogy szeretne szétválni, a vállalat egyik része kizárólag a csokoládé-, a másik pedig az italgyártásra fókuszálna. Ez 2008. május 2-án történt meg, az italgyártó cég Dr. Pepper Snapple Group néven működött tovább.

a vállalkozást, majd 1969-ben egyesült a Schweppes italgyártó céggel, így létrehozva aCadbury Schweppest, mely olyan termékekkel állt elő, mint aSunkist, a Canada Dry vagy aTyphoo Tea. 2007 márciusában a Cadbury Schweppes bejelentette, hogy szeretne szétválni, a vállalat egyik része kizárólag a csokoládé-, a másik pedig az italgyártásra fókuszálna. Ez 2008. május 2-án történt meg, az italgyártó cég Dr. Pepper Snapple Group néven működött tovább.2007 októberében a Cadbury plc bezárta Keynshamben működő gyárát, ezzel 500-700 munkahely szűnt meg. A termelést angol és lengyel üzemek vették át.

2009. szeptember 7-én a Kraft Foods 10,2 milliárd fontos ajánlatot tett a Cadburyért, de a tulajdonosok nemet mondtak, mivel szerintük ennél jóval többet ér a cég. A falánk óriás azonban nem adta fel és pár hónap múlva, 2010. február 5-ére a Cadbury részények 75%-át megvette a tőzsdén. Néhány hónappal ezelőtt az utolsó Cadbury sarj is lemondott, így mára az egyetlen ami a családot össze köti a csokoládéval - a mindig jól felismerhető aláírás a csokoládépapíron.

Feliratkozás:

Megjegyzések (Atom)